Rights groups concerned as likelihood of drowning increases on ‘most dangerous’ route and as conditions worsen in Libya.

Refugees and migrants are dying in the Mediterranean at a quicker rate than last year, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has reported, as rights groups raise alarm over abusive conditions in Libya – now the main country of departure.

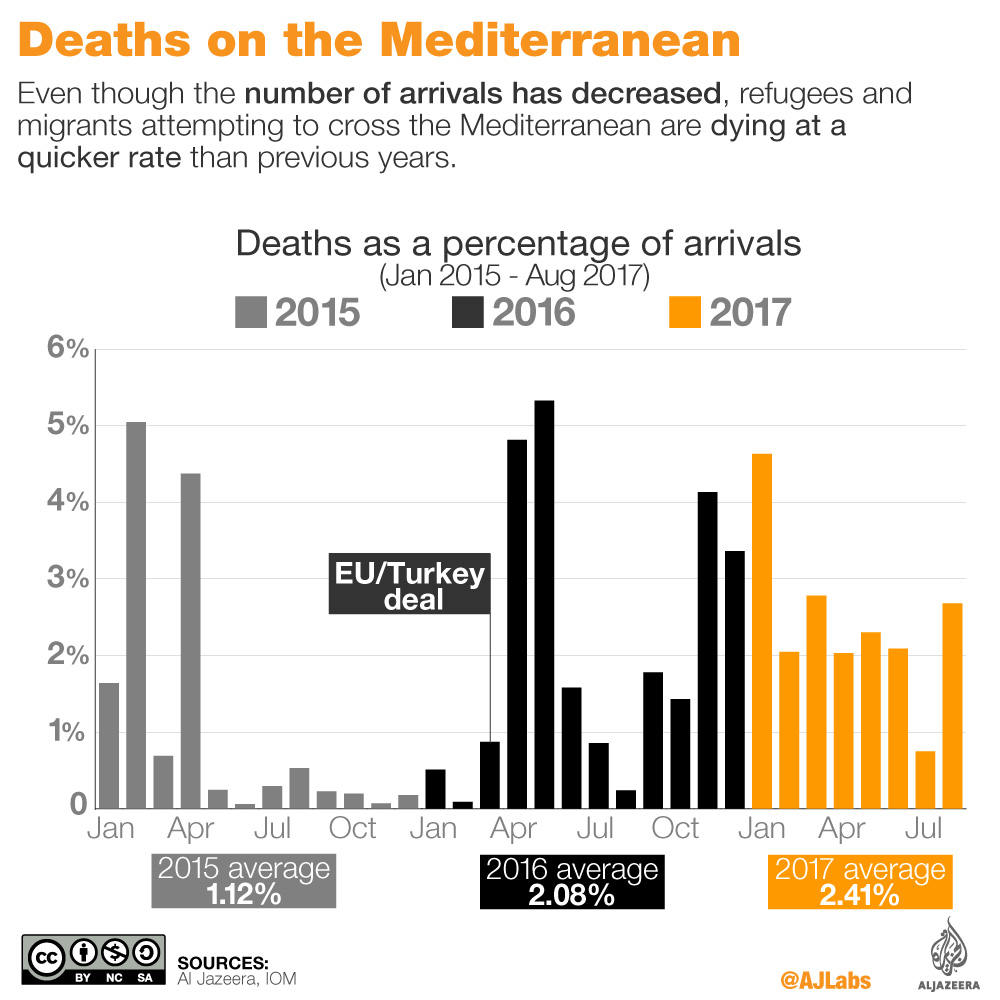

While fewer refugees have drowned so far in 2017 compared with the same period a year ago, the number of arrivals has fallen drastically – meaning that those who do set off from the Libyan coast have a greater chance of dying.

At least 2,550 refugees and migrants died from January 1 to September 13, 2017, compared with 3,262 from the same period in 2016, the IOM said – a drop of 22 percent.

However, arrivals to Europe have fallen much more sharply from 293,806 to 128,863 – a year-on-year decrease of 57 percent.

At this year’s rate, one refugee dies for every 50 who make it to Europe. Last year, one person died for every 90 who safely reached Europe.

“The rate of deaths for migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean was almost twice as high in 2017 than in 2016,” the IOM said in a recent report.

“Despite considerable policy and media attention and increased search and rescue efforts by a range of actors, the death toll in the Mediterranean has continued to rise … The rate of death increased from 1.2 percent in the first half of 2016, to 2.1 percent in the first half of 2017.

“Although fewer migrants crossed the Mediterranean in 2017, a higher percentage of those on this journey perished.”

The Central Mediterranean journey, from Libya to Malta or Italy, is now the most active refugee route for refugees.

In March last year, two events slowed the flow of Europe-bound refugees migrating from Turkey and Greece.

First, a string of countries effectively shut the Balkan route which allowed refugees to travel by land from Greece to Western Europe. The EU-Turkey deal also came into effect, pushing hopeful asylum seekers in Greece back to Turkey and closing the Aegean route. Most of those affected were from the Middle East and Asia.

Those attempting to travel to Europe now from Libya are mostly African, Moroccan or Bangladeshi.

“Part of this rise [in the death rate] is due to the greater proportion of migrants now taking the most dangerous route – that across the Central Mediterranean,” the IOM report stated.

Smugglers have also made the journey increasingly dangerous, forgoing boats for rubber dinghies, using less fuel and preventing refugees from carrying much drinking water, rights groups told Al Jazeera.

15,000 killed in four years

In the four years since October 2013, when these deadly journeys started making headlines, the Mediterranean crossing has claimed the lives of at least 15,000 refugees and migrants, accounting for more than half of the 22,500 refugees and migrants who have died or gone missing globally.

Those figures put into perspective statements by European officials, who have rushed to welcome the fact that fewer bodies are being pulled from the sea or washing ashore recently.

For example, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker made his third State of the Union speech to the European Parliament on September 13, claiming: “We have drastically reduced the loss of life in the Mediterranean.”

Juncker did also temper his claim, however, by calling on Europe to “urgently improve migrants’ living conditions in Libya”, and acknowledging the “inhumane” conditions at detention centres.

“Fewer departures from Libya mean more people in abusive situations in Libya itself,” Judith Sunderland, associate director for Europe at Human Rights Watch (HRW), told Al Jazeera.

Rights groups have for months documented widespread exploitation and abuse of thousands of refugees in Libya.

Although it is possible that not all refugees and migrants trapped in Libya fled violence at home, they are likely attempting to escape brutal conditions in the war-torn, insecure country, Sunderland added, citing reports of beatings, torture, sexual violence and forced labour.

NGOs have also condemned reports of the EU-backed Libyan coastguard shooting at aid workers and refugees at sea.

“In the Mediterranean, we currently witness a full-blown offensive against migrants and civil search and rescue actors, in which EU institutions and member states work hand-in-hand with their authoritarian allies in Libya to shut down the Central Mediterranean migration route,” said a spokesman from Alarmphone, a network of activist and migrant groups providing a 24-hour hotline for refugees in distress at sea.

“Currently, there is no reason whatsoever for celebration. The root causes for migration and flight have not changed.”

Italian officials are also among those celebrating lower arrivals figures, attributing the drop to tougher actions against smugglers.

“It’s not surprising,” said HRW’s Sutherland. “Italians would celebrate lower departures and then take credit for it – it’s a huge political issue in Italy. The country is in campaign mode with elections in 2018.”

The Western pushback against refugees was also boosted in February this year when the European Union in February signed a $215m deal with the fragile Libyan government to stop migrant boats, encourage voluntary repatriation and set up “safe” camps in Libya.

“Reducing the numbers of boats setting off from Libyan shores does not solve the issue, it simply pushes it back into Libya, and into the detention centres,” Marcella Kraay, a Doctors Without Borders (known by its French initials, MSF) coordinator on board the Aquarius rescue boat, told Al Jazeera.

“Nearly all people MSF search and rescue teams save from drowning on the Mediterranean have been exposed to an alarming level of violence and exploitation while in Libya: kidnap for ransom, forced labour, sexual violence and enforced prostitution, being kept in captivity or detained arbitrarily.”

The NGO says it has assisted women pregnant as a result of rape and treated people for violence-related injuries: broken bones, infected wounds and old scars from beatings and abuse.

“The EU needs to shift its strategy to put the security of refugees and migrants first,” said Kraay. “The EU member states should shift their focus from fighting symptoms and stopping people to finding solutions and assisting people … Injecting money without transparency, monitoring and accountability risks fuelling the detention business and the abuses.”

Looking ahead, rights groups are concerned that the number of people boarding flimsy dinghies from Libya could return to previous highs, with smugglers again endangering the lives of thousands more refugees.

“[Refugees] need to be allowed to leave these conditions in Libya. There needs to be legal and safe ways to reach the territories of the EU,” the Alarmphone spokesman told Al Jazeera.

Follow Anealla Safdar on Twitter: @anealla

[Disclaimer]