Biden’s first phone calls show where he’s looking — and it’s not at Israel

Unlike his predecessors, the US president has not called Middle East leaders in his first days, likely indicating what his administration will focus on: Neighbors and NATO.

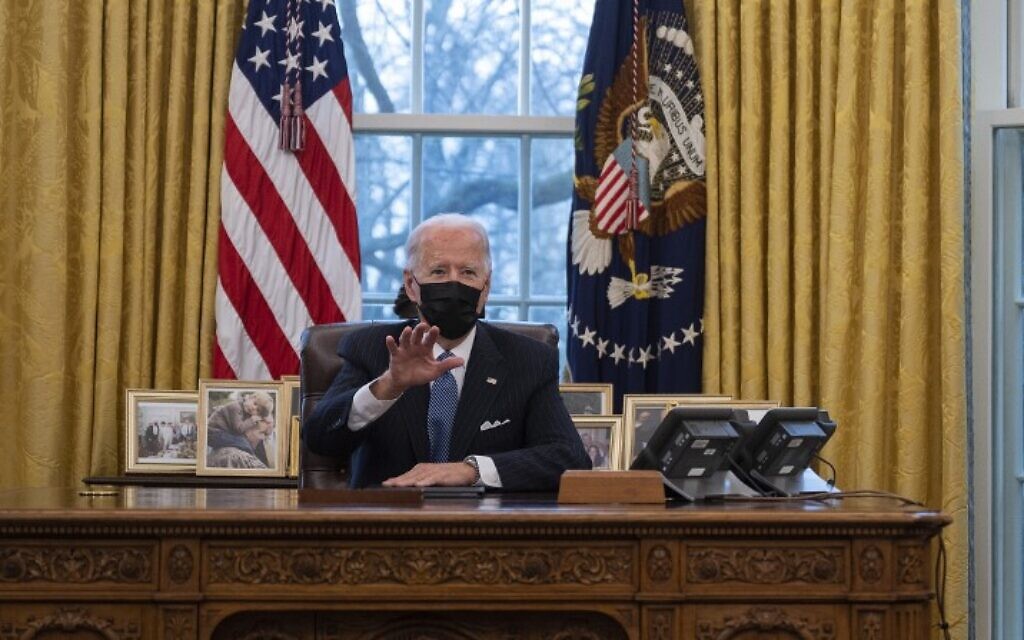

US President Joe Biden in the Oval Office of the White House on January 25, 2021. (JIM WATSON / AFP)

In his first week in office, US President Joe Biden has spent a considerable amount of time on the phone with other world leaders.

He has called London, dialed Berlin, and rang Moscow.

But as of Thursday morning Washington time, the new leader of the free world had yet to phone Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu or any Middle Eastern leader for that matter.

This is a marked departure from Biden’s two predecessors, Donald Trump and Barack Obama, who both spoke to Netanyahu and other regional partners in their initial round of calls.

The calls, or lack thereof, are not necessarily a sign of any particular tension or problem between the countries or between the leaders themselves. But a look at who Biden has been speaking to long-distance can provide some insight into the new president’s global priorities.

For better or worse, Israel is not among them.

Long-distance relationship

Biden’s first phone calls after the inauguration went to America’s neighbors.

His January 22 call with Canadian PM Justin Trudeau, Biden’s first as president, came after Trudeau expressed disappointment over Biden’s move to cancel the controversial Keystone XL pipeline.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at a news conference, January 8, 2020 in Ottawa. (Dave Chan / AFP)

Biden’s next call that day went to Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador. The Mexican leader, known by his nickname “AMLO”, had developed a close personal bond with Trump, and was one of the last world leaders to congratulate Biden on his victory. The phone call was an attempt to open a new page between the leaders, who will have to cope with confounding issues like trade and immigration.

Biden’s shifted his focus to Europe in his second round of calls. On January 23, he spoke with UK leader Boris Johnson, who also had a good working relationship with Trump. He spoke with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel over the next two days, both leaders who were doubtless relieved by Biden’s expressions of support for NATO and the US commitment to collective defense in Europe.

The messages underlined his promise to reverse Trump’s stance on NATO and its role as a bulwark against Russia. The ex-president was not averse to publicly haranguing NATO members to spend more on defense, and some reports indicated he had pondered withdrawing from the alliance.

The message was driven home on Tuesday with a call to NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, in which Biden pledged to “rebuild and reestablish our alliances, starting with NATO.”

In a rare move emphasizing the importance with which the new administration views the organization, the White House and NATO released a joint video of the call.

After making his support clear for America’s European partners, Biden turned to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Under Trump, the rhetoric around the US-Russia relationship was usually positive, but in practice, ties have reached a post-Soviet nadir.

The White House readout of the call stressed the new tone coming out of Washington, pointing out that Biden raised with Putin concerns over “the SolarWinds hack, reports of Russia placing bounties on United States soldiers in Afghanistan, interference in the 2020 United States election, and the poisoning of Aleksey Navalny.”

“President Biden made clear that the United States will act firmly in defense of its national interests in response to actions by Russia that harm us or our allies. The two presidents agreed to maintain transparent and consistent communication going forward.”

If the phone calls are a guide, the central thrust of Biden’s foreign policy out of the gate seems clear: Focus on trade and immigration with neighbors, deal firmly with Russia, and work through NATO partners while strengthening the alliance.

“This is about consolidating relationships at home, and with our most trusted allies across the Atlantic,” said Jonathan Schanzer, Senior Vice President at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. “One gets the sense that we’re addressing immediate domestic needs, and then from there looking to shore up the EU after four years of fairly tumultuous relationships, and then NATO, which has been somewhat rocky because of Trump’s pressure on a lot of these countries.”

Making a different call

Trump also made calls to the leaders of Mexico, Germany, France, and Russia within the first eight days of entering office.

But all those calls came after a conversation with Netanyahu on Trump’s third day in office. According to Netanyahu’s office, the conversation was “very warm,” and the two leaders discussed the Iran deal, the peace process, and “other issues” including an invitation to visit Washington.

Other initial calls Trump made were less pleasant. Instead of the traditional courteous — and rather bland — conversations that leaders have come to expect, Trump laid into traditional allies. He reportedly lambasted Australian PM Malcolm Turnbull over a deal the Obama administration had signed that would allow refugees from an Australian detention center into the US.

“This is the worst deal ever,” Trump told Turnbull.

US President Donald Trump (right) with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu prior to Trump’s departure to Rome, at Ben Gurion International Airport, May 23, 2017. (Kobi Gideon / GPO via Flash90)

Trump’s phone calls, both when they came and what they contained, turned out to be a reliable bellwether of his foreign policy.

He went beyond previous US administrations in his support for Israel, moving America’s embassy to Jerusalem, recognizing Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights, and defunding UN agencies both countries see as biased against the Jewish state.

He also focused on traditional American allies in Europe during his four years in office, but with a new message, taking them to task publicly and privately over their perceived unwillingness to contribute their fair share in maintaining a military deterrent against Russia.

Obama also set the tone with the phone calls he made in his first days in office. He kicked things off with calls to the Middle East on his first day in office, speaking to Egyptian, Israeli, Jordanian, and Palestinian Authority leaders. The Palestinians claim that the first call went to PA President Mahmoud Abbas.

The calls may have reflected world events happening then. Obama took office only two days after Israel ended Operation Cast Lead in Gaza (the timing of Israel’s withdrawal was probably no coincidence). Over one thousand Palestinian combatants and civilians died in the conflict, and it was certainly a pressing issue on Obama’s agenda.

But Obama’s phone calls were also an indication of his administration’s desire to bring a new approach to vexing problems in the Middle East. Like Biden, he promised to re-engage with the international community following eight years of George W. Bush. But unlike Biden, the focus of his effort was the Middle East, not Europe.

The president visited Turkey and Iraq in April 2009, then Saudi Arabia and Egypt in June. He gave two speeches, one in Ankara and one in Cairo, offering “a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world, one based on mutual interest and mutual respect.”

US President Barack Obama speaks with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in January 2012. (Peter Souza/White House/File)

But the administration’s focus on the Middle East proved a challenge for Israel’s leadership. Netanyahu butted heads with Obama over settlements, peace talks with the Palestinians, the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and most prominently, Iran’s nuclear program.

The personal animus between the leaders was on full display during joint press conferences, and Netanyahu’s speech before Congress assailing the impending nuclear deal with Iran infuriated the president and many in his party.

Take a message

Netanyahu can breathe a sigh of relief that he wasn’t in Biden’s first round of calls. Though the relationship between the leaders is expected to be warmer than those during Obama’s tenure, Biden was never going to be as aligned with Netanyahu’s priorities as Trump was.

With clear differences of opinion over the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and settlements, the best Netanyahu can hope for right now is an American focus on domestic issues like the economy and COVID-19, and on Russia and China in the international sphere.

That’s not to say the Biden administration has blocked out the region entirely. US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken is already deep in the weeds on dealing with Iran and has held talks with his Israeli counterpart Gabi Ashkenazi. On Thursday, Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, the head of the US Central Command, visited Israel, in what some have seen as a message to Tehran.

But what the commander in chief does sets the agenda. And so far, Biden has shown that he is in no rush to spend energy or political capital on the Middle East. He has signed a record 22 executive orders in his first week in office, none of which have anything directly to do with Middle East policy. His inaugural speech, 22 minutes long, dedicated only two sentences to foreign policy at all.

“We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again,” he promised from the dais. “Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s challenges.”

US President Joe Biden speaks after being sworn in as the 46th President of the US, at the US Capitol in Washington, January 20, 2021. (Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP)

That was it. Nothing on Iran, nothing on the peace process, nothing on the Middle East.

Biden’s turn away from the Middle East is a continuation of broader trends in American public opinion and in the threats the country faces.

America became deeply involved — many would say bogged down — in the Middle East after the September 11, 2001 attacks. As the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq turned into insurgencies and America’s death toll mounted, voters began to ask why American blood and treasure was being wasted in far-flung countries, especially with pressing problems at home. Obama began reducing America’s military commitment to the region, and Trump accelerated the process. There is currently no appetite among US leaders from either party to invest significant resources in the Middle East.

In addition, the US has recognized that the most pressing international threats it faces are not from Islamic terrorism, but from Russia and China. This view is evident in American strategic documents, including the 2018 National Defense Strategy.

“The central challenge to US prosperity and security is the reemergence of long-term, strategic competition by what the National Security Strategy classifies as revisionist powers,” it reads. “It is increasingly clear that China and Russia want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model — gaining veto authority

over other nations’ economic, diplomatic, and security decisions.”

US military forces are being designed and structured to face a multi-domain threat from near-peer adversaries like Russia and China.

Still, the Middle East has a way of overtaking world events and insinuating itself into the agenda of US presidents. Eventually, a call will come, but until then, one doubts that Netanyahu will be sitting by the phone waiting for it.

Source: https://www.timesofisrael.com/bidens-first-phone-calls-show-where-hes-looking-and-its-not-at-israel/