Isaiah’s Signature Uncovered in Jerusalem

King Hezekiah is one of the most important kings in the history of Israel. While scholars debate the historicity and literary embellishment of the reigns of David and Solomon, the reign of Hezekiah witnessed the defining event that engendered the tradition of Jerusalem as the inviolable city of God—an event corroborated by the extra-Biblical account inscribed on the Sennacherib Prisms. Despite the conflicting details, Sennacherib’s inability to destroy Jerusalem confirmed both Hezekiah andJerusalem as God’s chosen. And it was the prophet Isaiah’s participation in the episode, and Hezekiah’s trust in his counsel, that is credited with the salvation of Jerusalem from the Assyrian menace.

When King Hezekiah was crowned king of Judah, in 727 B.C.E., he maintained the policy of his father, Aḥaz, who had asked the Assyrian king to come and save him from Peqaḥ ben Remaliyahu, king of Israel, and Reẓin, king of Aram-Damascus. These two kings had attacked Judah in concert and besieged Jerusalem (see 2 Kings 15:36–37). Hezekiah stayed loyal to the Assyrian king Sargon II (727–705 B.C.E.), who ruled during most of Hezekiah’s reign, while the surrounding kingdoms of Israel, Ḥamat, and those of the Philistines—one after the other—rebelled, were defeated, and became Assyrian vassals. It was only after Sargon II’s death, in 705 B.C.E., that Hezekiah rebelled fully against Assyria. Yet according to the Assyrian annals, in 712 B.C.E. Hezekiah also had been involved in a rebellion— led by the Philistine city of Ashdod—against Sargon II, which resulted in the conquest of Ashdod and its transformation into an Assyrian vassal. However, only a heavy tax payment was seemingly imposed on Hezekiah, who probably paid on time, thus saving himself and his kingdom from a similar fate. Subsequently, Hezekiah led regional preparations for a rebellion against Assyria, which eventually broke out after Sargon II’s death.

Biblical Archaeology Review is the world leader in making academic discoveries and insights of the archaeology of the Biblical lands and textual study of the Bible available to a lay audience. Every word, every photo, every insight—it can all be yours right now with an All-Access membership. Subscribe today!

During most of his reign, Hezekiah’s policy of avoiding confrontation with Sargon II—and the relative freedom he experienced by not becoming an Assyrian vassal—enabled him to focus on Judah’s internal affairs. Under his rule, Judah became a center for all the people of Israel, including the inhabitants of the former Kingdom of Israel, and the Temple in Jerusalem played a major role as the holiest place for all. Hezekiah is described in 2 Kings as the greatest king, second to King David, “his father”: “There was no one like him among all the kings of Judah, either before him or after him” (2 Kings 18:5).

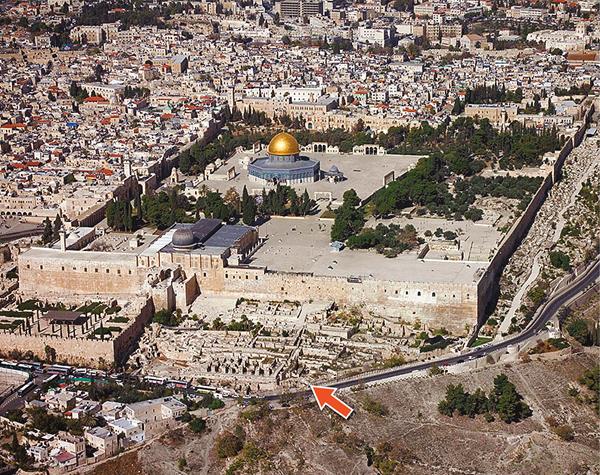

In Hezekiah’s time, two palaces had been already functioning in Jerusalem for more than 200 years: King David’s Palace in the City of David, used as the Lower House of the King (Nehemiah 12:37), and King Solomon’s Palace in the Ophel, used as the Upper House of the King (Nehemiah 3:25). The Upper House of the King was built in the open area of the Ophel—to the south of the Temple Mount and about 820 feet north of the fortified City of David.1 These palaces served as comprehensive complexes and were used both as the residence of the king and his family and for the multiple activities related to the king and the kingdom. The Temple and the new palace complex in the Ophel were surrounded by a massive city wall during King Solomon’s reign (1 Kings 3:1).2

Both palace complexes probably underwent multiple changes and renovations since their construction, but a significant, reinforcing enterprise, undertaken by King Hezekiah in the Lower House of the King, also known as the House of Millo (2 Kings 12:20 [v. 21 in Hebrew]; 2 Chronicles 24:25),3 was particularly worth mentioning in the Bible, due to its sophisticated and extensive nature (2 Chronicles 32:5).4 Under Hezekiah’s orders, this complex functioned as a palace-fortress, reinforced as part of his defensive preparations against the imminent Assyrian attack (2 Chronicles 32:5).

Structures built by King Solomon (1 Kings 3:1) were found beautifully preserved in an area about 328 feet long and 33–82 feet wide in the northeastern outskirts of the Ophel. These structures consist mainly of a segment of the fortification wall with the city gate and its large tower, and parts of royal buildings that were integrated within the fortification line. Due to the steep slanting of the bedrock in this area facing the Kidron Valley, the fortification wall and its integrated buildings were built on particularly massive foundations set straight on bedrock. These structures were preserved to a height of 13–16 feet, uncovered at only 3–7 feet beneath the present surface level.

One of these buildings, adjacent to the city gate on the northeast, was discovered during the 1986–1987 excavations.5 The building’s ground floor, preserved to a height of about 13 feet, was last used by the royal bakers up to its destruction by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E. The sophisticated administration of the royal bakery required a high official in charge and a well-organized supply system of high-quality food products, such as flour, oil, and sweetening agents like bee-honey, date-honey, fig-honey, and fresh and dry fruits. It also required a well-organized storage place and baking spaces. Within the ground floor of this building, which we named the Royal Building or the Building of the Royal Bakers, were found some large jars (pithoi). On the shoulder of one of these jars, an inscription in ancient Hebrew indicates that it belonged to the high official in charge of the bakery (the end of the word “bakery” is missing, but its reconstruction in this manner is quite certain). On another large jar, which most likely contained date-honey, a palm tree design was incised. It is evident that the building was used by the royal bakers at the end of the First Temple period, and it may have had the same use in Hezekiah’s time.

Some idea of the building’s function during Hezekiah’s reign is provided by the many finds revealed during the 2009 excavations at the foot of its outer, southeastern wall.6 There, only two small, undisturbed areas remained (each about 3 by 3 ft and 3 ft high)—remnants of the piled debris accumulated outside the building—since Herodian and Byzantine constructions destroyed the rest. This debris yielded fragments of pottery vessels, ivory inlays, zoomorphic four-legged figurines, and two kinds of anthropomorphic figurines—one with pinched face and the other a female with a prominent bosom of clear fertility significance. The assemblage also included four-winged and two-winged lmlk seal impressions on jar handles and 34 seal impressions stamped on a soft piece of clay (bullae). Most of the bullae bore Hebrew names, but some were free-standing bullae used as receipts.7

Each of the Hebrew bullae, measuring about 0.4 inches in diameter, had been stamped with a seal bearing the name of its owner. These were created by first placing soft clay on a tied ligature and linen sack or papyrus, whose negative impressions are clearly seen on the bulla’s reverse side, and then pressing the seal against the clay. Among the bullae found in the debris, only five show papyrus negative impressions on their reverse side. One of these is the bulla impressed with the personal seal of King Hezekiah.8

Seven of the bullae found in the debris, all with coarsely woven linen negative impressions on the reverse, appear to have belonged to the relatives of an important individual named Bes, a name of an unclear meaning neither found in the epigraphic material of the period nor known from the Bible.

Three of these bullae belonged to one of Bes’s grandsons named “Yeraḥmiel son of Nahum son of Bes” and one to a second grandson named “Aḥimelekh son of Pel[?] son of Bes.” The names on the other three bullae, although clearly belonging to sons and grandsons of Bes, could not be identified. That all the bullae of the Bes family mention three instead of the usual two generations, emphasizes the status of Bes as the head of the family, most likely well known in the manufacture of the products held within these coarse linen sacks—or in the administration associated with it. Although only five names of the Bes family were deciphered, including the name Bes itself, none contains elements of the divine name Yahweh, pointing, perhaps, to the non-Judahite origin of the family.

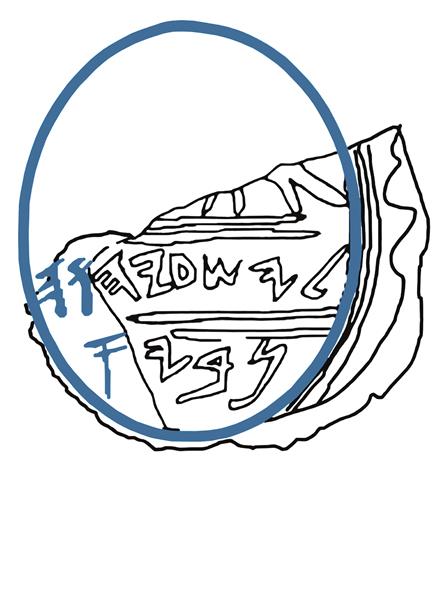

Alongside the bullae of Hezekiah and the Bes family, 22 additional bullae with Hebrew names were found. Among these is the bulla of “Yesha‘yah[u] Nvy[?].” The obvious initial translation, as surprising as it might seem, suggests that this belonged to the prophet Isaiah.9 Naturally, this bulla is far more intriguing than all the others found adjacent to Hezekiah’s bulla.

All the undisturbed Iron Age layers excavated in this area were wet-sifted, a process through which earth debris is washed with water. The use of this technique resulted in the rescue of hundreds of small finds which otherwise would not have come to light, including all the bullae from the area.

Also wet-sifted was the material from the lowest half-meter, down to bedrock, of the same Iron Age layers, where a foundation trench was cut for a wall of a Herodian vault. This material, coming from the northwestern end of the foundation trench,10 included the bulla of Yesha‘yah[u] Nvy[?]. It was located only 6.5 feet southeast from the wall of the Building of the Royal Bakers, while the bulla of King Hezekiah was found about 13.1 feet southeast from the same wall; thus, less than 10 feet separated the bulla of Yesha‘yah[u] Nvy[?] and the bulla of King Hezekiah.

The seal impression of Yesha‘yah[u] Nvy[?] is divided into three registers. The upper end of the bulla is missing, and its lower left end is slightly damaged. The surviving portion of the top register shows the lower part of a grazing doe, a motif of blessing and protection found in Judah, particularly in Jerusalem, present also on another bulla from the same area.11 The middle register reads “leyesha‘yah[u]” (Hebrew: לישעיה[ו]; [belonging] “to Isaiah”), where the damaged left end most likely included the letter vav (w; Hebrew: ו). The lower register reads “nvy” (Hebrew: נבי), centered. The damaged left end of this register may have been left empty, as on the right, with no additional letters, but it also may have had an additional letter, such as an aleph (’ ; Hebrew: א), which would render the word nvy’ (Hebrew: נביא), “prophet” in Hebrew. The addition of the letter aleph (’) creates the occupation name (like Baker, Smith, or Priest) for “prophet,” nvy’ in plene spelling. The defective spelling of the same word, nv’ (without the vowel yod), is present on an ostracon from the Judahite site of Lachish.12 Whether or not the aleph was added at the end of the lower register is speculative, as meticulous examinations of that damaged part of the bulla could not identify any remnants of additional letters.

Finding a seal impression of the prophet Isaiah next to that of King Hezekiah should not be unexpected. It would not be the first time that seal impressions of two Biblical personas, mentioned in the same verse in the Bible, were found in an archaeological context. In our City of David excavations (2005–2008), the seal impressions of Yehukhal ben Sheleḿiyahu ben Shovi and Gedaliyahu ben Pashḥur, high officials in King Ẓedekiah’s court (Jeremiah 38:1), were found only a few feet apart.13 Furthermore, according to the Bible, the names of King Hezekiah and the prophet Isaiah are mentioned in one breath 14 of the 29 times the name of Isaiah is recalled (2 Kings 19–20; Isaiah 37–39). No other figure was closer to King Hezekiah than the prophet Isaiah.

Could it therefore be possible that here, in an archaeological assemblage found within a royal context dated to the time of King Hezekiah, right next to the king’s seal impression, another seal impression was found that reads “Yesha‘yahu Navy’ ” and belonged to the prophet Isaiah? Is it alternatively possible for this seal NOT to belong to the prophet Isaiah, but instead to one of the king’s officials named Isaiah with the surname Nvy?

Biblical Archaeology Review is the world leader in making academic discoveries and insights of the archaeology of the Biblical lands and textual study of the Bible available to a lay audience. Every word, every photo, every insight—it can all be yours right now with an All-Access membership. Subscribe today!

With that said, when considering the identification of this seal impression as that of the prophet Isaiah, some major obstacles arise.

Without an aleph at the end, the word nvy is most likely just a personal name. Although it does not appear in the Bible, it does appear on seals and a seal impression on a jar handle, all from unprovenanced, private collections.14 It also appears as bn nvy (“son of nvy”), most likely a name, on two bullae from the end of the First Temple period (early seventh century B.C.E.) stamped with the same seal, both found together in a juglet from Lachish.15

The standard layout of names on bullae is composed of the owner’s name and his father’s name, with or without the additional word bn(“son of”) before the father’s name. Due to lack of space on the small bullae, the word bn (“son of”) was often omitted. Thus, the absence of the Hebrew word for “son of” before the word nvy, like in our bulla, is not uncommon—if indeed Nvy was his father’s name. However, a lack of space was apparently not the case in our bulla, since the letters in both registers were written spaciously, and no attempt was made to find space for the two letters bn.

Avigad suggested that the name nvy is derived from the toponym Nov (Hebrew: נב), a known town of priests (see 1 Samuel 21:1; 1 Samuel 22:11, 19; Nehemiah 11:32; Isaiah 10:32).16 If our inscription indeed records a toponym derived from the site of Nov, it would still be missing the definite article (“h-” or “ha-” in Hebrew), as seen in the Bible when a toponym is added to a name, such as in “Aḥiya Hashiloni” (Aḥiya the Shilohite), or “Aḥitophel Hagiloni” (Aḥitophel the Gilohite). However, more significant is the fact that no other seal or seal impression with a personal name followed by the name of a place—with or without a definite article—has ever been found.

The completion of the existing writing of “nvy” with an aleph at the end—then reading navy’(“prophet”)—also faces the problem of the lack of the Hebrew definite article “h” (“the”) at the beginning of the word, as seen in the bulla of “the healer” (hrp’) (Hebrew: הרפא) from the City of David, which reads “[to ṭbšlm] son of zkr the healer” (הרפא זכר בן [לטבשלם]).17

Nevertheless, Reut Livyatan Ben-Arie, who studied the bullae from the Ophel with me, suggests that there is enough space for two more letters at the end of the second register: a “w” (vav), the last letter in the name Yesha‘yahu, and an “h,” the definite article “the” for the word navy’ (“prophet”), rendering it hanavy’ (“the prophet”). One can wonder why the seal’s designer would choose to insert the definite article at the end of the second register instead of at the beginning of the word navy’ on third register, where there seems to have been enough space. But, as strange as it may seem to us, this division of words is not unusual in ancient Hebrew writing. In fact, a good example of this can be seen in King Hezekiah’s bulla, where the name of his father, Aḥaz, spreads over two registers, with the last letter pushed into the lower one. Thus, the spreading of a word over two registers on seals seems to have been accepted, if not common.

Except for the bulla of the healer and perhaps that of Yesha‘yahu, no other bullae with the Hebrew definite article “h” at the beginning of a title have been found in an excavation; a few unprovenanced bullae reading “the scribe” and “the priest” are known from private collections.18 On the other hand, no seals or bullae with single-word titles such as “prophet” (nvy’), “scribe” (spr), or “priest” (khn) that lack the definite Hebrew article “h” at the beginning are known from excavations or private collections.

The Bible shows support both for the use of the definite article with a title and for its omission. For example, the title “secretary” (mzkyr) appears both with (2 Samuel 20:24) and without (2 Samuel 8:16) the definite article “h,” with reference to the same individual. The same is true for the title “scribe” (swpr), which appears both with (Isaiah 36:22) and without (2 Samuel 8:17) the definite article “h,” with reference to two different individuals.

Likewise, prophets did refer to themselves as nvy’ without the definite article “h,” as we learn from the prophet Elijah, who says, “I alone am left a prophet (Hebrew: נביא) of YHWH” (1 Kings 18:22). On the other hand, in merely two chapters of the Book of Kings, Isaiah is mentioned as “Isaiah,” “Isaiah the prophet,” “Isaiah the prophet the son of Amoẓ,” “Isaiah the son of Amoẓ,” and “Isaiah the son of Amoẓ the prophet” (2 Kings 19–20), and in each occurrence the definite article “h” appears with the word nvy’ (Hebrew: הנביא). It would seem, therefore, that there is no strict rule for the use of a title with reference to a persona. In light of the fact that titles appear both with and without the definite article, it is not surprising that the title nvy’ would appear on this bulla without it.

A very recent discovery from Jerusalem demonstrates the inconsistent use of the definite article “h” in both titles and professions on inscribed texts. A new bulla, dating to the end of the First Temple period, was uncovered during the IAA excavations conducted opposite the Western Wall of the Temple Mount.19 The bulla depicts two figures standing opposite one another, with the writing lsr‘r (Hebrew: לשׂרער; lesar‘ir) below them in Hebrew, indicating that the bulla belonged “to the governor of the city,” most likely that of Jerusalem. This discovery contributes greatly to the known assemblage of bullae with professional titles inscribed on them and is of special interest to us since it is missing the Hebrew definite article “h” before the word ‘ir(“city”). This title, with the definite article “h,” appears several times in the Bible, where it is also present in the plural form “governors of the city,” as in 2 Chronicles 29:20, which relates events from Hezekiah’s reign. This new information further strengthens our argument that the presence of the Hebrew definite article “h” placed before titles and professions on bullae was neither indispensable nor consistent in that period, but was subject to the discretion of the author.

This seal impression of Isaiah, therefore, is unique, and questions still remain about what it actually says. However, the close relationship between Isaiah and King Hezekiah, as described in the Bible, and the fact the bulla was found next to one bearing the name of Hezekiah seem to leave open the possibility that, despite the difficulties presented by the bulla’s damaged area, this may have been a seal impression of Isaiah the prophet, adviser to King Hezekiah.

The discovery of the royal structures and finds from the time of King Hezekiah at the Ophel is a rare opportunity to reveal vividly this specific time in the history of Jerusalem. The finds lead us to an almost personal “encounter” with some of the key players who took part in the life of the Ophel’s Royal Quarter, including King Hezekiah and, perhaps, also the prophet Isaiah.20

Source: https://members.bib-arch.org/biblical-archaeology-review/44/2/7

[Disclaimer]