BC-Putin’s-Oil-Price-Gambit-Has-Run-Out-of-Road , Clara Ferreira Marques

(Bloomberg Opinion) — In the eyes of Moscow hardliners, the shale boom that turned the U.S. into a leading oil exporter has also encouraged Washington’s belligerence. Back in early March, low prices were a welcome means of pushing American producers over the edge; Russia’s bolstered state finances and its lower-cost oil companies meant it could take the pain.

But that was then.

Now, the unfolding coronavirus epidemic has forced the country into a shutdown that will last until the end of April, while dealing an unprecedented blow to oil demand. It’s a double whammy just as President Vladimir Putin, whose approval ratings have been slipping, prepares to extend his stay at the top. An output-cutting deal with other producing nations, even one that can merely cushion the revenue drop, is now desirable, to stop the economy — and the president’s popularity — from fraying further. Achieving that on the Kremlin’s terms will be another matter.

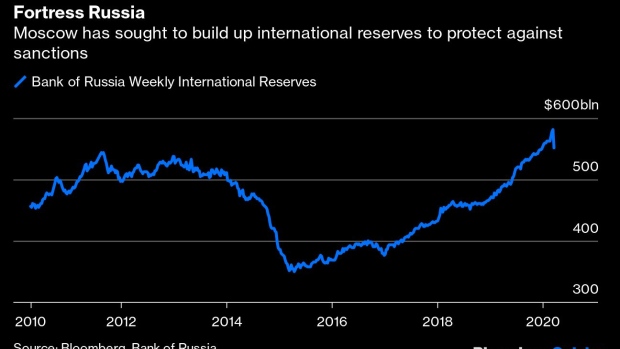

Russia is certainly less vulnerable than in the past, in part thanks to financial buffers encouraged by U.S. sanctions. Like Saudi Arabia, with whom Moscow is engaged in a damaging output standoff, it has used high oil prices to cut its external debt. Fiscal prudence has created budget surpluses, while foreign currency reserves have increased. Corporate debt in foreign currency has fallen. The country is even more self-sufficient in food.

Yet oil prices have halved this year. Brent is trading at $34 per barrel, with West Texas Intermediate and Urals crude, Russia’s export blend, below $30. That’s grim news for Moscow, and not just because its budget balances with the benchmark value at just above $40, or because Putin started the year with promises of significant social spending. The budget can be reworked with $20 oil — and indeed already is. Russia can still borrow.

At current prices, though, profit margins begin to look thin even for Russian producers, for whom it costs less than $20, including capital spending, to extract and ship a barrel, and which also benefit from a falling rouble and flexible taxes. And it’s not just about the state budget: Energy investment will fall, affecting employment and consumption. Combined with shelter-in-place orders for Russia’s citizens, prospects for the broader economy look bleak. The nationwide shutdown could cost 1.5%-2% of GDP, according to the Bank of Russia. The government’s worst-case scenario last month had the economy shrinking by as much as 10%. That’s a dramatic drop for a country that has already seen disposable incomes falter.

The logic of squeezing shale producers hasn’t disappeared, nor has the clout of Igor Sechin, the pugnacious boss of Rosneft Oil Co., the state-backed producer. His weight has arguably increased with January’s change of government. With global oil demand likely to remain well below 100 million barrels per day for some time, Russia wants a bigger share of what remains. But at this rate, the country’s own ambitious projects, like the Bazhenov formation, the world’s largest shale oil resource, look untenable.

The real wild card here has been the coronavirus. Not just the direct economic hit, but also Putin’s distant initial reaction and the lack of a fiscal boost, which means he hasn’t seen the sort of rallying effect in the polls that has helped U.S. President Donald Trump and other political leaders.

Nigel Gould-Davies, at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, suggests the risk is a repeat of Putin’s Kursk debacle two decades ago, when his perceived leadership failure at the time of the submarine tragedy triggered widespread criticism. This isn’t a threat to the plan to change the constitution to allow him to stay on, but his “father of the nation” gambit may be harder to implement, especially if Russia’s under-resourced health system buckles.

An oil output deal, even today, won’t fix the crude price problem, given we now have the biggest supply overhang in history. It’s difficult too for Russia to cut, even if it wants to. Saad Rahim, chief economist at commodity trader Trafigura, estimates that Moscow will want to target a reduction of just 500,000 to 1 million barrels per day at most, as its large number of older, more marginal fields means that anything more would risk wastage and long-term damage to reservoirs. And there is no compensation for lost volume from Moscow’s wealth fund. For some analysts, it makes little sense for Russia to yield now, when many people have yet to feel the pain at home.

Yet the longer this drags on, the less financial capacity Russia, and its banks, will have to provide support for businesses and households. To make matters worse, the country has limited oil storage too.

Moscow is pragmatic. But Trump will need to make some concession-like noises at least on American production cuts, to help Putin save face. Not easy, but given the shut-ins already triggered by the price fall, also not impossible, with the help of U.S. state energy regulators. Other non-OPEC producer nations may have to join in. The threat of tariffs, a favorite Trump tool, would by contrast be more irritating than effective, at least for Russia, which ships the vast majority of its oil to destinations outside the U.S.

Absent that, there’s pain ahead for everyone.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

Source: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/putin-s-oil-price-gambit-has-run-out-of-road-1.1418374

[Disclaimer]