Tremors change life in Volcano: With no end in sight, stress levels rise

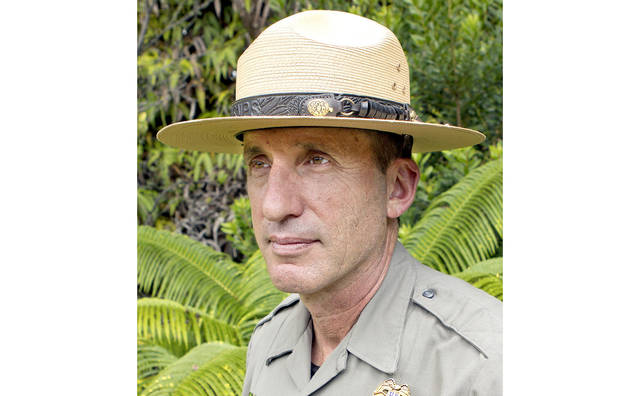

John Broward, chief ranger for Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

If the lights by the window shake, it’s a magnitude 3. If the water sloshes out of the catchment tank, it’s a magnitude 5.

Living in a village rocked by hundreds of earthquakes — or, more accurately, earthquake-like tremors — each day, Volcano residents have developed their own unique measurements to determine which quakes are nothing to worry about and which ones might be something more.

“Every time, you wonder if this one’s going to be the big one, if this one isn’t going to stop,” said Volcano resident Tim Freeman.

Freeman was one of dozens of Volcano residents who attended a community meeting Thursday evening at Cooper Center, where representatives of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory explained the ongoing changes at Kilauea summit.

While attendees at the meeting were composed and responded to the speakers with good humor, one question was repeated over and over: “When will it end?”

The answer, repeated as many times, was “Nobody knows.”

“We don’t know if this is the beginning, the middle or if we’re getting close to the end,” said HVO geologist Don Swanson.

For several weeks, ground subsidence around the summit caldera following the recession of the lava reservoir has caused the volume of the crater to expand by approximately 10 million cubic meters per day, said HVO research geophysicist Kyle Anderson.

This subsidence is accompanied by semi-regular pressure explosions, and temblors which register as earthquakes of up to magnitude 5.4.

The explosions happen roughly once per day. Following an explosion, seismic activity lessens for a time, but additional tremors of increasing intensity occur throughout the day until another explosion settles the mountain for the next cycle.

The constant cycle is nerve-wracking for the village’s inhabitants.

“I’ve been staying outside all the time because I can’t stand listening to my house shake,” said resident Antoinette Bullough.

Lydia Meneses, another resident who lives less than 3 miles from the caldera, said the repeated quakes are taking their toll on her home.

“I’ve noticed the hairline cracks are getting more hairlines,” Meneses said.

More worrisome, Meneses said, is the surface of Piimauna Drive, the only road in or out of her subdivision. While the road is still passable, cracks in the surface have developed and expanded since the quakes began, leading Meneses to worry that eventually she might have no way out.

“People don’t understand what we’re going through,” Bullough said, explaining that neighborhood dogs, spooked by the shaking, bark incessantly, while the larger tremors are nearly impossible to sleep through.

“It’s a bit unnerving,” said Jim Wilson, a resident of Volcano for 25 years. “But there’s nothing any of us can do about it.”

During Thursday’s meeting, John Broward, chief ranger for Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, said he was confident that the park will reopen eventually, although the park will be drastically changed when it does. The ever-widening crater already has swallowed a parking lot, with Jaggar Museum — now stripped of its exhibits — likely to follow.

However, HVO representatives reassured residents that the caldera collapse is not expected to spread far from the summit. Cracks in Volcano road surfaces are entirely caused by repeated stress — i.e., constant shaking — rather than volcanic fissures or sinking land.

Residents remain uneasy though, and with far fewer visitors to Volcano now that the park is closed, residents and business owners wait in a constantly shaking limbo for things to return to normal.

“It’s more stressful than annoying right now,” Wilson said. “Not seeing any end to it is what makes it so stressful.”

Email Michael Brestovansky at mbrestovansky@hawaiitribune-herald.com.