Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency in 2016 with a pledge to bring down illegal immigration, famously blaming undocumented migrants from Mexico for a host of problems, including drugs and crime. In the four years since, how has this rhetoric translated into a wider immigration policy? -Getty Images

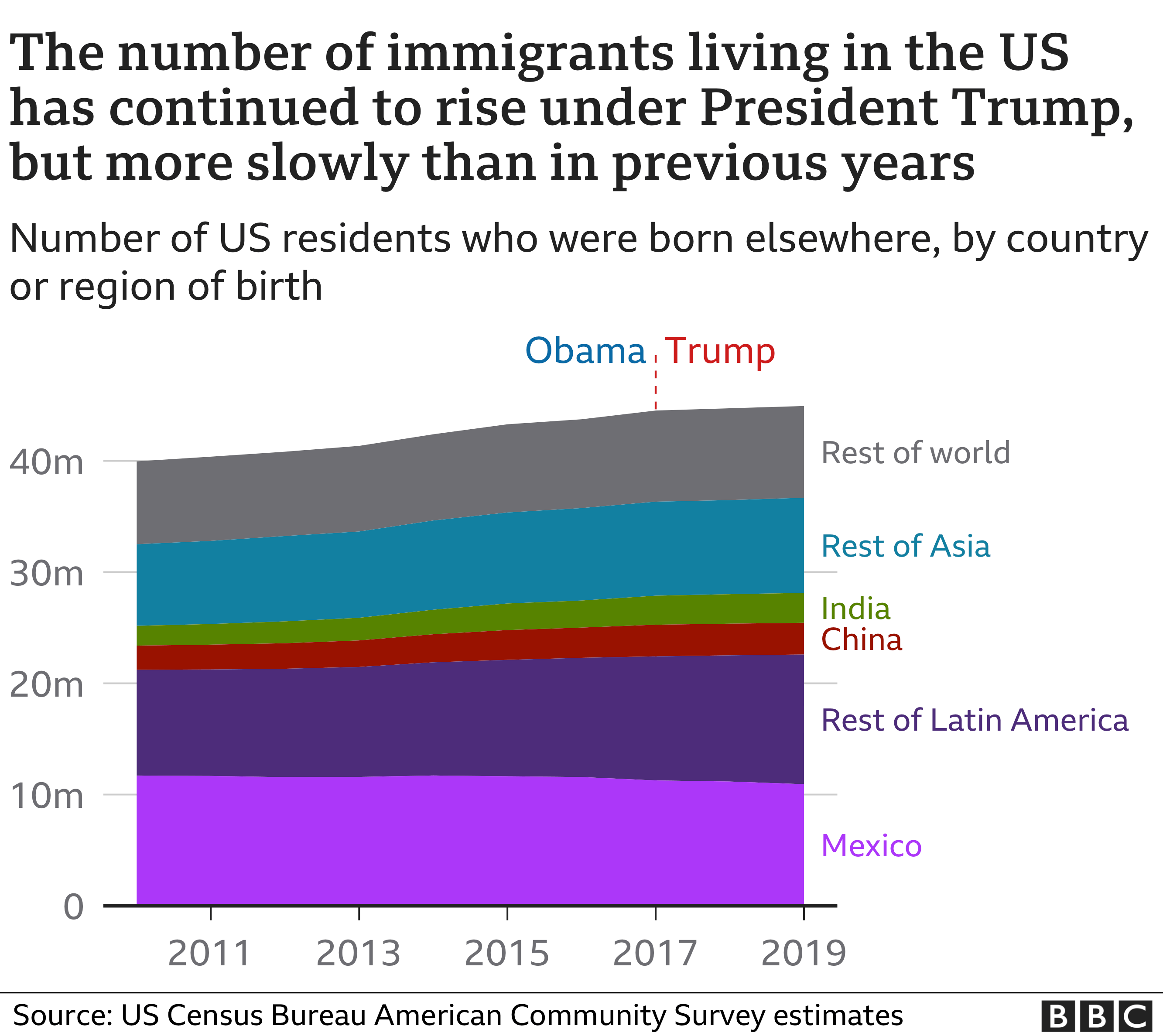

The number of foreign-born people living in the US has risen by about 3% from 43.7 million the year before Mr Trump’s election to about 45 million last year.

But this rise conceals a big shift in the largest group by far within this population – those who have moved to the US from Mexico. Having remained at nearly the same level for years, the number of people living in the US who were born in Mexico has fallen steadily since Mr Trump’s election.

While this dip was more than offset by an increase in the number of people who have moved to the US from elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean, demographers at the US Census Bureau have estimated that net migration – the number of people moving to the US minus those moving out of the US – has fallen to its lowest level for a decade.

This is partly due to lower levels of immigration, but also because more people who were born outside the US are moving back overseas, according to Anthony Knapp of the US Census Bureau.

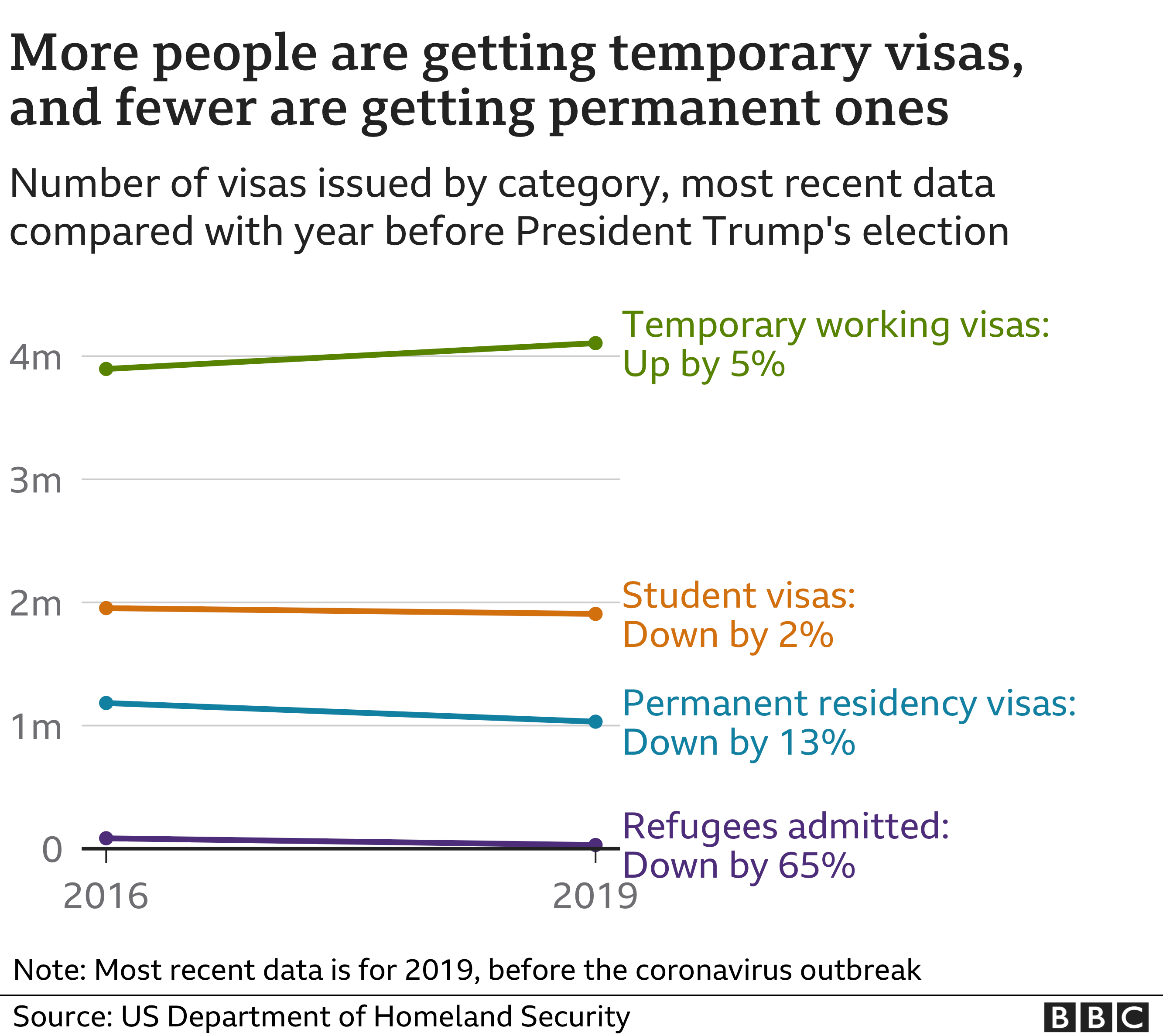

Beneath this trend there are some important changes to the visa system.

Mr Trump has allowed more people to come to the US temporarily for work, but made it harder for people to settle permanently in the US. The reduction in permanent visas, from about 1.2 million in 2016 to about 1 million in 2019, has primarily affected family members of US citizens and residents hoping to join their relatives, with the number of permanent visas sponsored by employers largely unchanged.

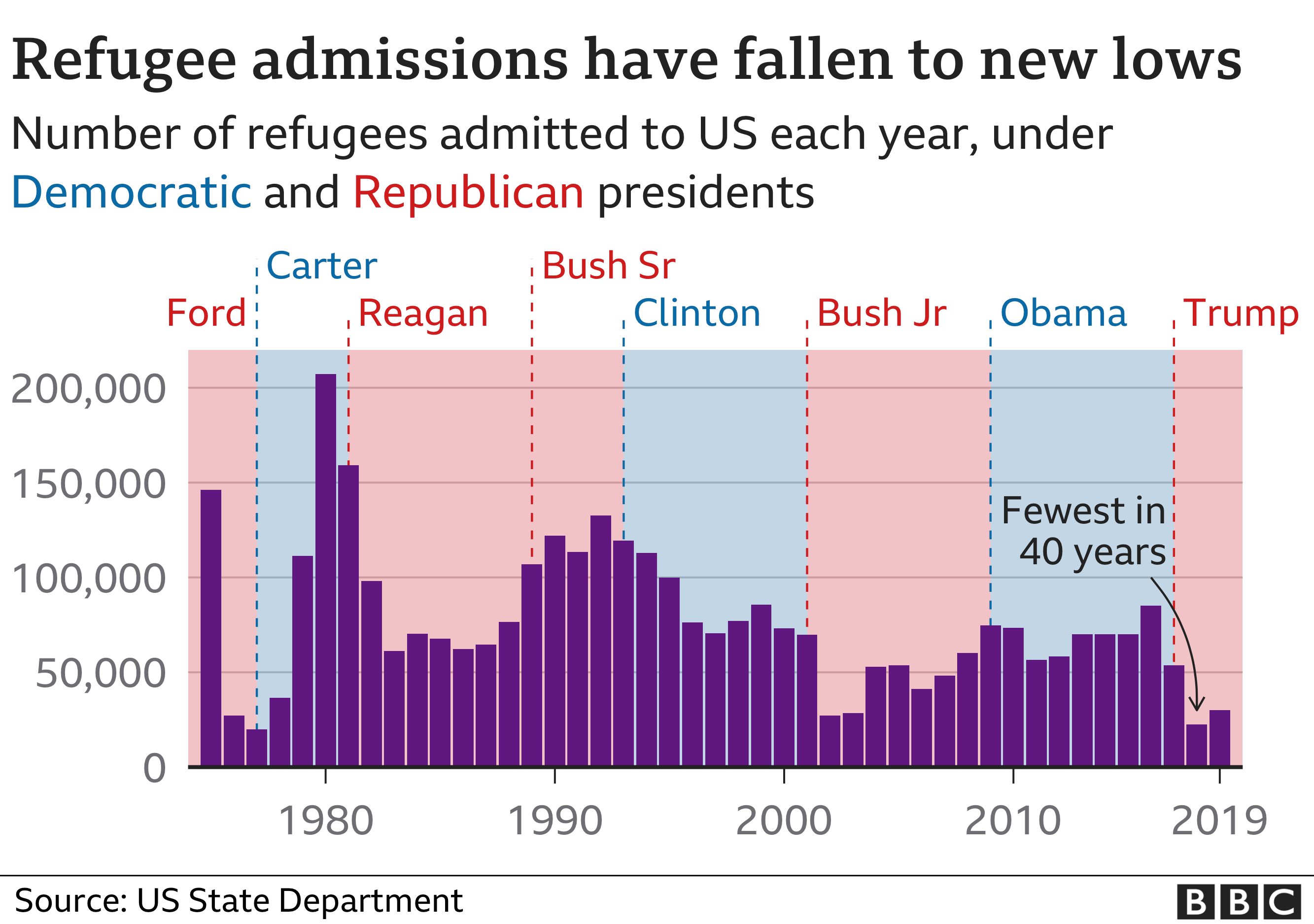

Although more people are affected by this, in percentage terms his most significant change to immigration policy has been to lower the number of refugees admitted to the US.

The number of people admitted to the US as refugees each year is determined by a system of quotas, the size of which are ultimately defined by the president. People seeking to move to the US as refugees must make their applications from outside the country, and need to convince US officials that they are vulnerable to persecution at home.

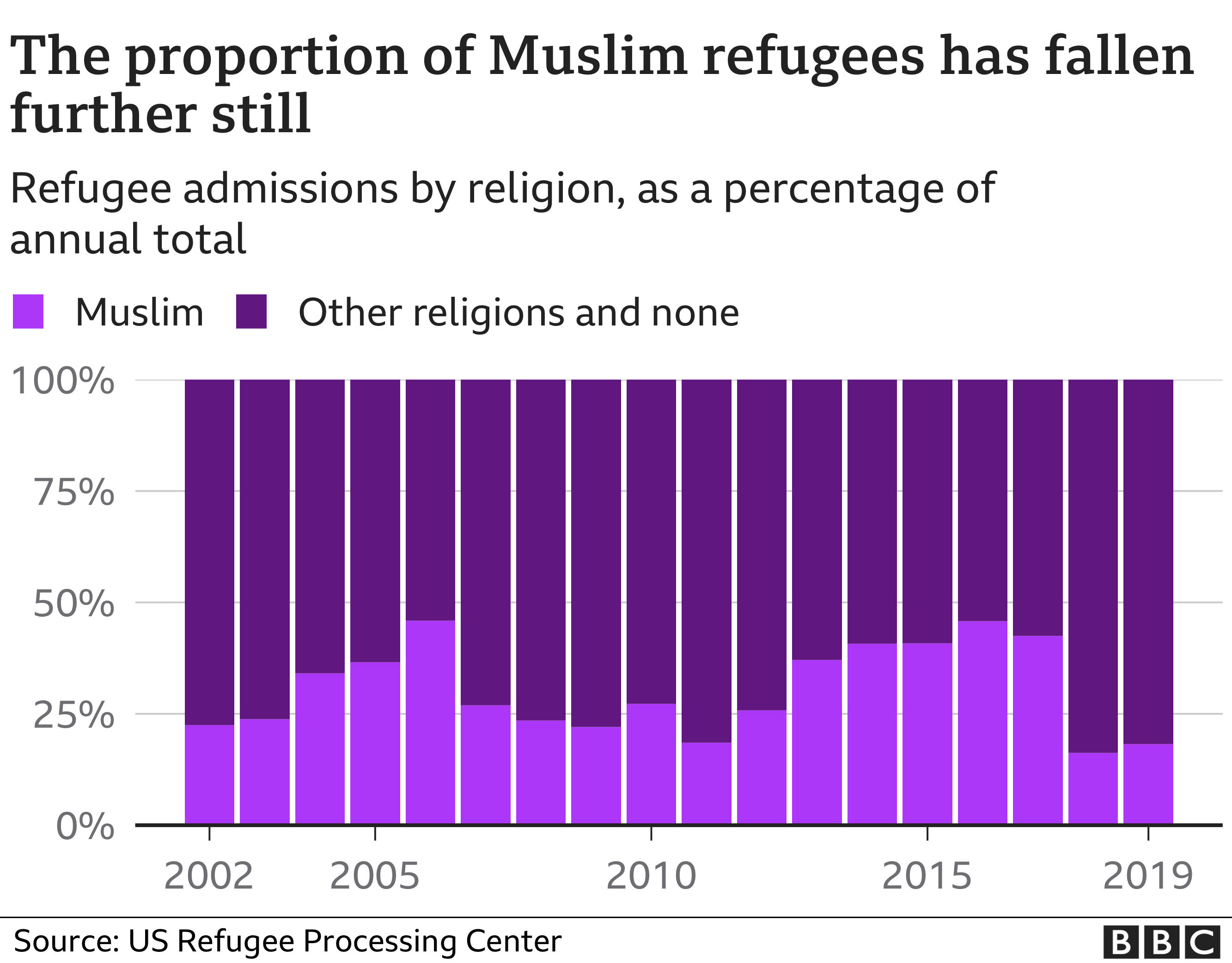

Mr Trump’s hostility to any immigration from Muslim-majority countries is well known – he once pledged to enact a “complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” – and a reduction in refugee quotas proved easier to implement than an outright ban, which became mired in legal challenges.

As a result, the number of refugees admitted from a number of majority-Muslim countries, including Iraq, Somalia, Iran and Syria, fell almost to zero soon after he took office.

Curbing visas and refugee admissions is not the only way to reduce the number of people entering the country, and Mr Trump has also sought to make it harder to move to, or remain in, the US without any relevant documentation.

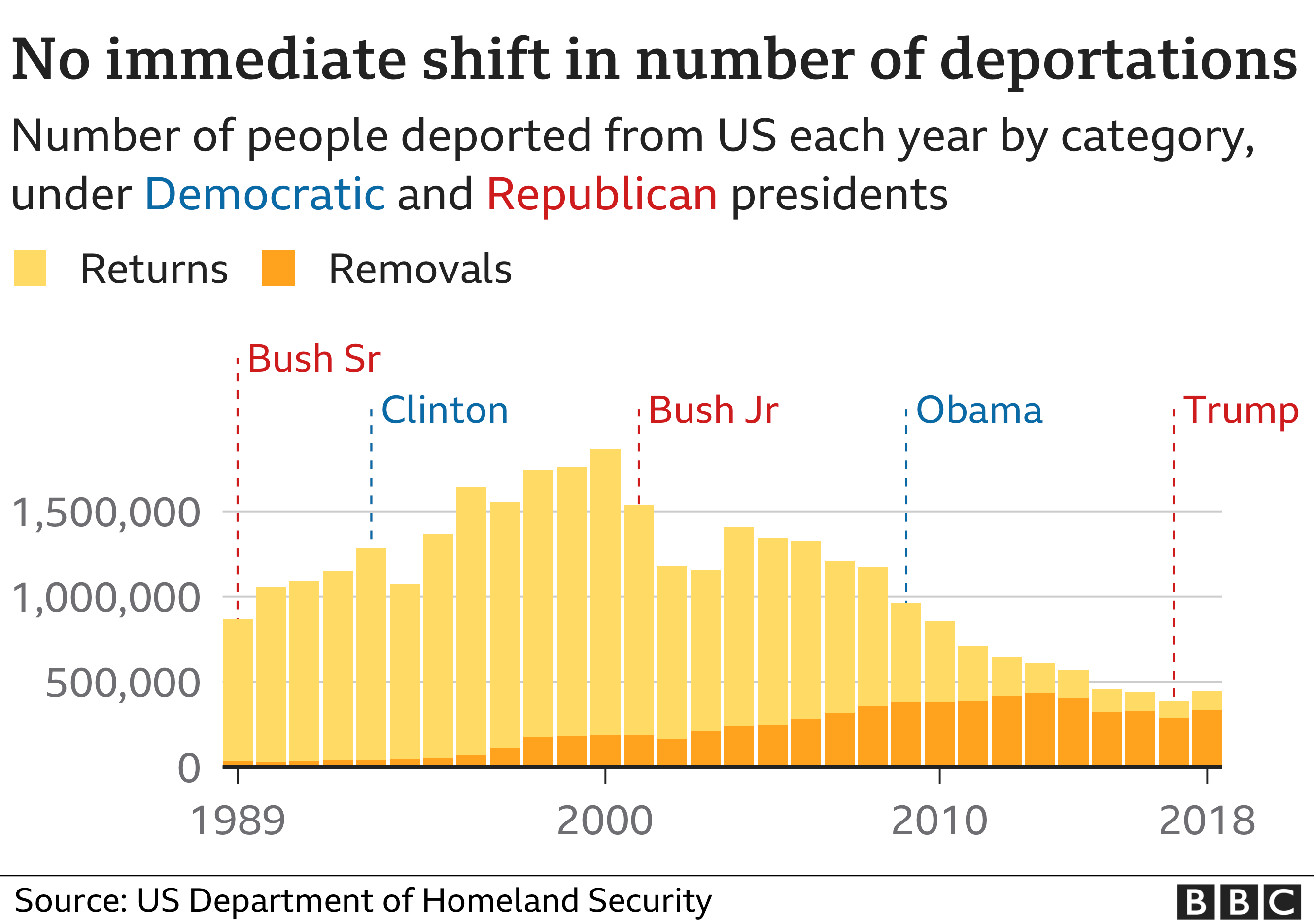

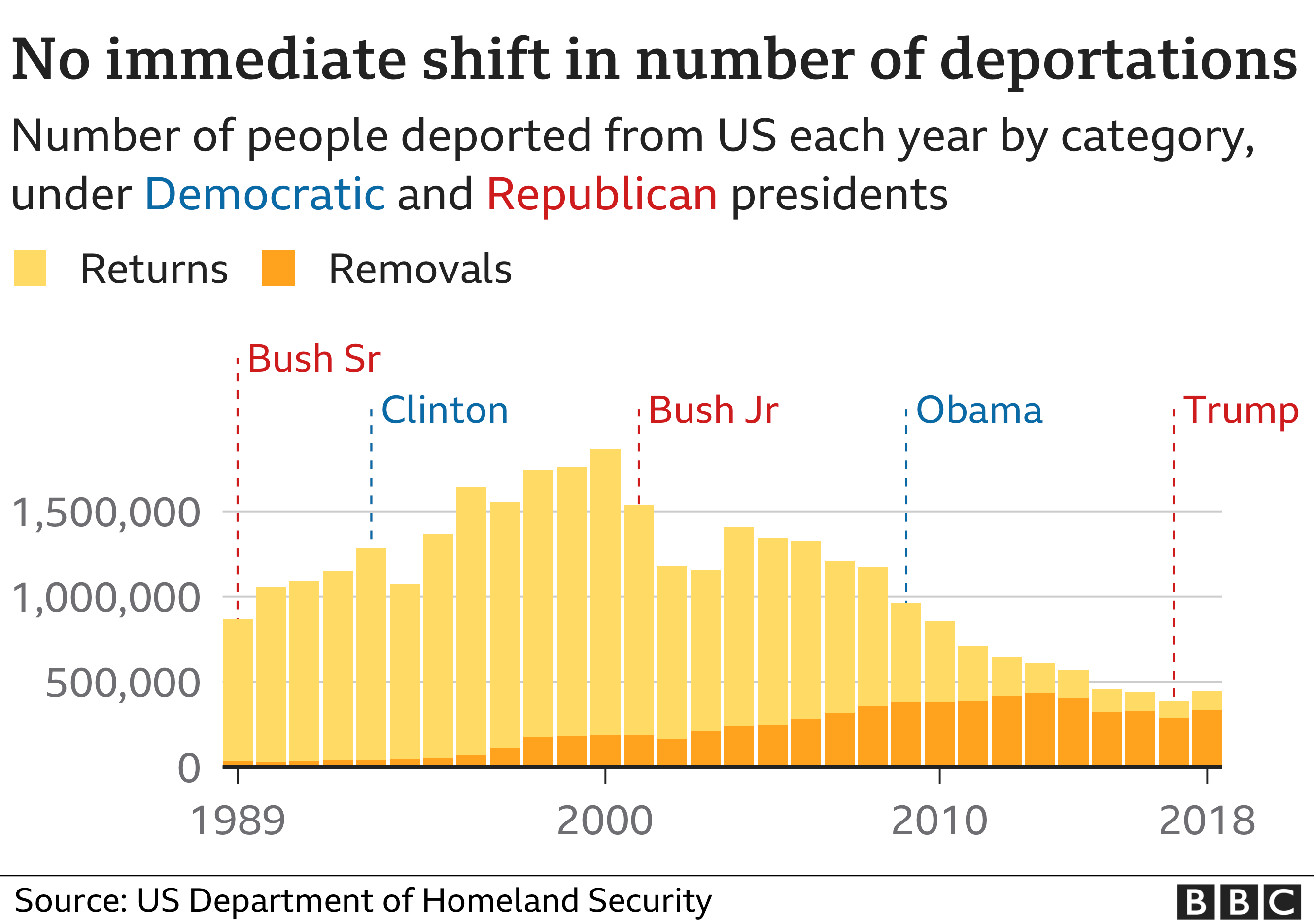

However, this is more difficult than it might seem. To understand what has happened during President Trump’s tenure, we first need to get to grips with what the official statistics on deportation mean, and they are broken down into two categories.

People are said to be “removed” if they are taken out of the country under the authority of a court order, and people are “returned” if they are refused admission while trying to cross the border, or asked to leave the country without a court order.

Being removed has a lasting legal consequence, making it much harder to gain re-entry to the country. But many people who have been returned across the US-Mexico border simply tried to enter the US again at a later date. President Obama escalated a policy enacted by his predecessor, President George W Bush, to step up removals – particularly of those who had been accused or convicted of criminal offences.

President Trump has not brought about any significant changes to the number of people in either deportation category compared with his predecessor.

The US Immigration, Customs and Enforcement agency, which handles most deportations, has described the current rate of removals as “extremely low”, blaming a lack of resources and “judicial and legislative constraints”, among other things.

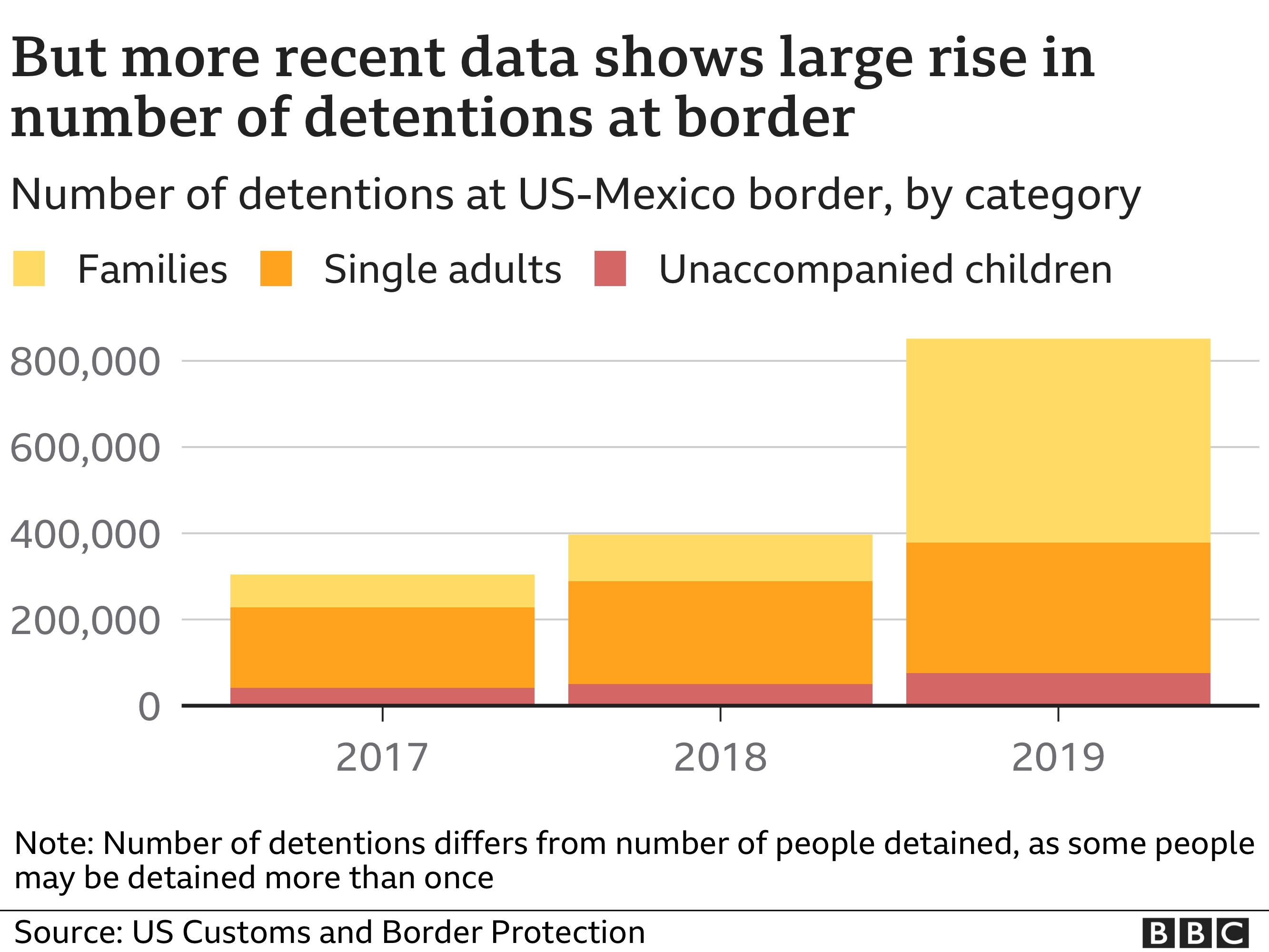

The agency is also under pressure at the Mexican border, where the administration’s changes to asylum policy have resulted a long backlog of cases, sometimes with families separated and children held in detention centres, and asylum seekers being returned to Mexico to await the processing of their claims.

Despite widespread media coverage of the border crisis, the data for 2019 suggests that would-be migrants have not been deterred – the number of detentions at the border was more than double the number for the previous year, driven largely by a large rise in the number of families attempting to get across.

This shift is likely to translate into a significant rise in the returns numbers for 2019, which are due to be released in the next few months.

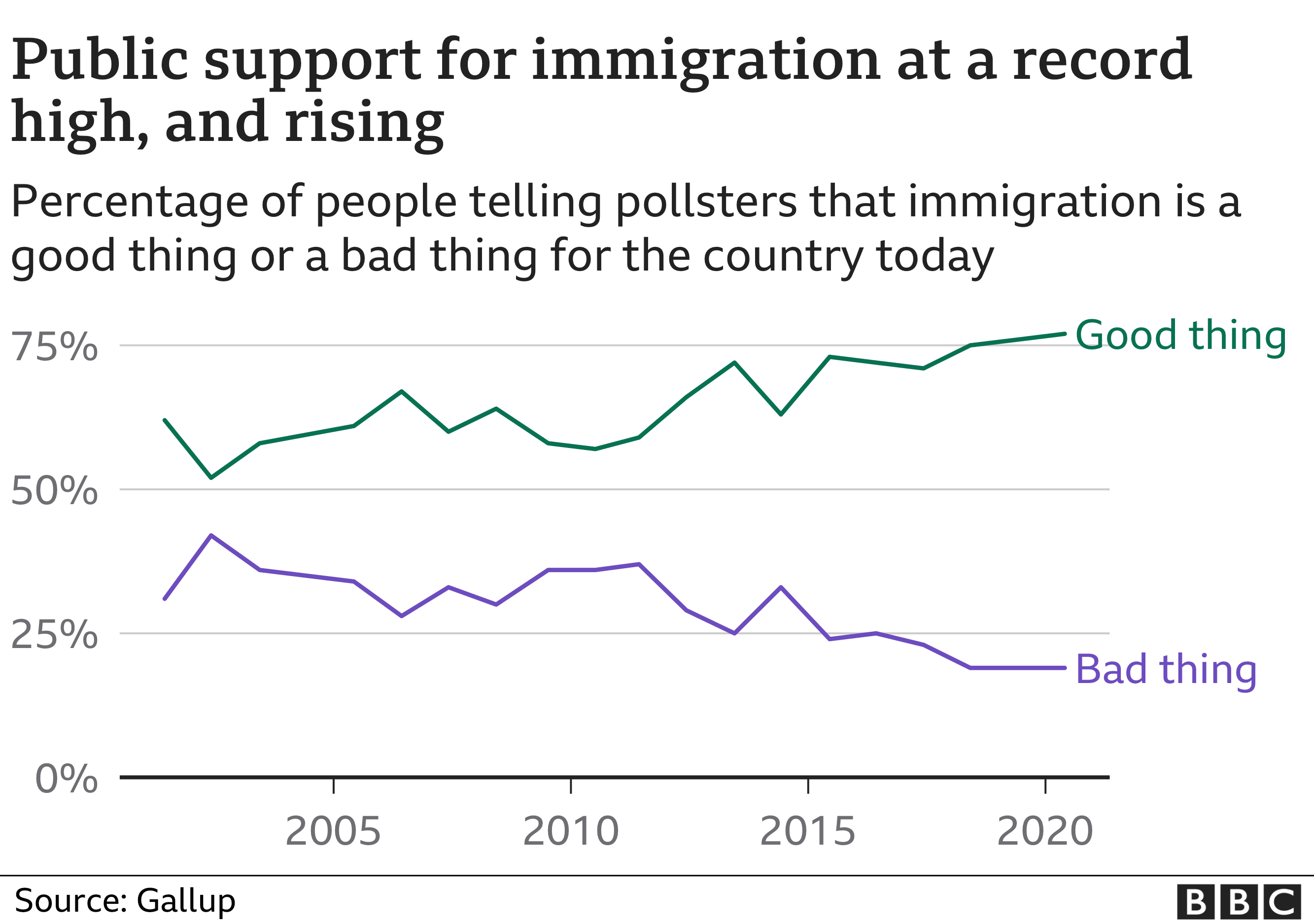

One interesting question is whether President Trump’s tough stance on immigration is still a major selling point among his supporters. The number of people telling pollsters that immigration is a bad thing has fallen steadily since he took office, with many former detractors apparently now believing it is generally good for the US.

Although there remains a gulf between Democratic and Republican voters on the issue, with Republicans far less likely to see immigration in a positive light, and far more likely to want stricter curbs on illegal immigration, the trend among both groups is the same.

Mr. Trump will be hoping that there remain enough Republican supporters of his approach to help push him past the winning post on election night.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2020-54638643

[Disclaimer]